Resumen

La comprensión lectora y las estrategias metacomprensivas representan un desafío en la educación superior, por lo que se diseñaron Sistemas Inteligentes de Tutorías (SIT) para que los estudiantes aprendieran a optimizar ambas habilidades. Este estudio evaluó el impacto de un programa SIT con y sin acompañamiento docente frente a un grupo control, para lo cual se utilizó un diseño experimental que midió la comprensión y la metacomprensión antes y después de la intervención. Los participantes que recibieron SIT mostraron mejoras significativas en la metacomprensión, pero solo aquellos con tutor humano obtuvieron mejores avances en la comprensión lectora. Estos resultados indican que, aunque el entrenamiento con SIT potencia la metacomprensión, la presencia de un tutor es clave para que esos beneficios se traduzcan en un mejor desempeño en la comprensión de textos.

Palabras clave:

comprensión lectora; enseñanza asistida por ordenador; enseñanza superior; sistemas inteligentes de tutoría; tutoría

Abstract:

Reading comprehension and metacomprehension strategies pose a persistent challenge in higher education; consequently, Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS) have been developed to help students optimize both skills. This study assessed the impact of an ITS program, delivered with and without instructor support, against a control group using a pretest-postest experimental design to measure comprehension and metacomprehension. Participants who engaged with the ITS exhibited significant improvements in metacomprehension, whereas only those who received human tutoring showed superior gains in reading comprehension. These results suggest that, although ITS training alone enhances metacomprehension, the presence of a human tutor is critical for converting those gains into improved text comprehension.

Keywords:

computer-assisted instruction; higher education; intelligent tutoring systems; reading comprehension; tutoring

1. Introduction

In higher education, reading comprehension and metacomprehension strategies represent central challenges for academic performance and student autonomy. Despite advances in educational technologies, a gap remains between mastering deep reading skills and students’ ability to accurately assess their own understanding processes. Several studies at the primary and secondary levels have shown that Intelligent Tutoring Systems (ITS) facilitate the development of cognitive and metacognitive strategies (Azevedo et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2019). However, there is still a lack of empirical research that examines the effectiveness of these systems specifically in university students and that compares different modalities of instructor support.

For this reason, the present article is based on the premise that the interaction between an ITS and a human tutor could enhance both reading comprehension and metacomprehension in higher education students. This research line originates from prior work demonstrating that, while ITS alone improves metacomprehension, only the presence of a human guide ensures sustained gains in deep-text comprehension (Hollander et al., 2022). In this context, we describe and evaluate an ITS program designed to teach and automate strategic reading tasks, supplemented with in-person tutoring sessions, compared to a group using the same system autonomously and a third control group. The general objective of this study is to analyze the impact of ITS on improving reading comprehension and metacomprehension in college students, as well as to explore their perceptions and experiences regarding the use of these tools.

Using an experimental approach with a 3×2 mixed-factorial design, this study explored differences in reading comprehension and metacomprehension across three groups (ITS with tutor, ITS without tutor, and control) and two time points (pretest and postest). Prior to the intervention, all participants completed a standardized reading comprehension test and a metacomprehension questionnaire validated for university populations (Guerra García & Guevara Benítez, 2013; McCarthy et al., 2018). During the five-week program, the ITS with tutor and ITS-only groups attended on-campus ITS sessions of 60 minutes twice weekly, with the ITS with tutor group receiving an additional weekly 30-minute in-person tutoring session. The control group continued with traditional lectures and reading activities without ITS access. After the five-week period, a postest was administered to all students, and ITS usage data were recorded (total interaction time, number of attempts per item, and correct/incorrect responses).

2. Literature review

In the last decade, the educational field has experienced considerable progress thanks to the implementation and expansion of information and communication technologies. These technologies have allowed higher education to transcend the classroom, transforming the conception and practice of educational processes. University students now encounter a combination of in-person education and virtual teaching environments. Online education has undergone substantial expansion in recent years, and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 significantly accelerated the transition to virtual learning, especially across higher education institutions. This mode of virtual education considers the learner as an active agent that develops professional and personal competencies autonomously (Sancho Gil et al., 2018). However, the adoption of this modality has also posed new challenges for higher education institutions. Among the proposals to address this type of learning are faculty training (Ayuso-del Puerto & Gutiérrez-Esteban, 2022; Balla-Paguay et al., 2022; Ruiz Domínguez & Area Moreira, 2022), the creation of virtual teaching fields, the promotion of digital literacy (Shafiee Rad, 2025; Zhou et al., 2025; Sá & Serpa, 2020), and the development of hybrid, online, or flexible modalities that require new competencies and literacies different from traditional ones (Arner et al., 2021; Cerezo et al., 2020; Choi et al., 2023), integrating analog and digital learning (Buckingham, 2015).

Reading comprehension is crucial in university, enabling students to grasp complex texts, conduct research, and engage in academic discussions. However, several studies have shown that many college students face difficulties in reading comprehension, which can affect their academic performance (Carretti et al., 2014; Clinton-Lisell et al., 2022). In this context, metacomprehension has become a topic of interest in educational research. Metacomprehension refers to students’ ability to reflect on and regulate their own reading comprehension processes, that is, to monitor, evaluate, and adjust their comprehension during reading (Baker, 2016; Kendeou et al., 2009). Metacomprehension is crucial for students to identify and overcome difficulties that may arise during reading, such as lack of understanding of concepts, confusion, or lack of connection between ideas.

Recent scholarship in Latin America has highlighted a persistent gap in higher-order reading skills among university students, particularly around critical comprehension. Research indicates that while undergraduates can generally retrieve explicit information and sometimes make inferences, their ability to evaluate arguments or engage critically with academic texts remains limited. Ramirez-Altamirano et al. (2023) explored metacognition as a reading strategy in first-year students, revealing that, while some awareness of reading processes was evident, participants encountered difficulties engaging in deeper analytical activities.

Barandica Sabalza’s systematic review (2023) demonstrated that critical thinking and metacognitive strategies are frequently promoted in language learning, yet critical reading itself is less consistently developed. To address these challenges, several pedagogical interventions have been designed around metacognitive approaches and reflective reading practices. In a 2025 study of Peruvian universities, Uculmana Cabrejos and Fernández Martínez (2025) reported that students perceive tools such as summarizing, concept mapping, and self-reflection to be beneficial for understanding and organizing academic texts. However, the same study emphasized that transitioning from comprehension to evaluation necessitates deliberate guidance. Similarly, Barandica Sabalza (2023) observed that numerous classroom initiatives enhance both literal and inferential comprehension; yet their impact on critical reading is inconsistent and often transient, frequently requiring ongoing instructional support to be sustained.

A substantial body of research points to the importance of contextualized teaching and institutional scaffolding in sustaining improvements in critical comprehension. Ramirez-Altamirano et al. (2023) concluded that, in the absence of structured curricular or pedagogical frameworks designed to promote deeper engagement, students’ metacognitive skills may not necessarily translate into enhanced critical reading performance. This view is corroborated by studies conducted with Colombian undergraduate students, which have demonstrated both potential gains and persistent obstacles in developing critical reading skills within the context of English as a Foreign Language (Castaño-Roldán & Correa, 2021). Collectively, these findings imply that the advancement of critical reading in higher education necessitates integrated strategies that combine metacognition, disciplinary relevance, and continuous instructional support.

ITS based on information and communication technologies have emerged as a promising tool to improve reading comprehension and metacomprehension in university students (Atun, 2020). These systems offer an interactive and adaptive learning environment that provides immediate and personalized feedback to students, allowing them to develop reading comprehension and metacognition skills more effectively (Mousavinasab et al., 2018). Studies show that ITS improves reading comprehension and metacomprehension across various educational settings, including higher education (Guo et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). These systems use techniques such as knowledge modeling, automatic detection of comprehension difficulties, and adaptive feedback to help students develop effective reading and self-regulation strategies.

For instance, Azevedo et al. (2022) elucidate how MetaTutor employs multimodal data (interaction logs, eye tracking, and facial expressions) to assist university students in establishing objectives, perpetually monitoring their advancement, and methodically appraising their learning process. By comparing adaptive scaffolding conditions with non-adaptive ones, the authors demonstrate that adaptive prompts encourage more strategic engagement and better calibration between students’ confidence and their actual performance. Furthermore, pedagogical agents that suggest specific actions (e.g., taking notes or self-assessing at key moments) significantly reinforce these effects. In a similar manner, TuinLec (Vidal-Abarca et al., 2014), a web-based ITS, was implemented in combination with a clear text-structure strategy to enhance students’ reading comprehension. A six-month quasi-experimental design was employed in which primary school students were assigned to either the TuinLec intervention or a control based solely on the curriculum. Multinomial-logistic regression revealed that those in the TuinLec condition were significantly more likely to form well-organized memory structures (e.g., problem-solution, comparison, and main-idea schemata) and to obtain higher comprehension scores than their peers receiving standard instruction. The findings emphasize the efficacy of integrating online scaffolding with strategy teaching in effectively restructuring students’ cognitive processes and achieving substantial enhancements in memory organization and reading performance.

A review of the extant literature reveals several limitations that hinder the generalization of findings and justify the need for further research. For instance, Cerezo et al. (2020) employed a quasi-experimental design comprising a single 90-minute MetaTutorES session, which precludes the evaluation of long-term effects on reading comprehension. Furthermore, the sample comprised students with and without learning difficulties but did not incorporate a well-defined control group to compare the support modalities (Cerezo et al., 2020). In a similar vein, McCarthy et al. (2018) incorporated metacognitive prompts within ITSART. However, their pre-post design was marred by a limited number of sessions, and they did not explicitly examine the impact of a human tutor versus the autonomous use of ITS. This limitation hinders our understanding of how instructor interaction enhances reading comprehension outcomes. Mousavinasab et al. (2018) conducted a systematic review which highlighted that the majority of ITS for language skills focus on primary and secondary education populations or general learning contexts. This leaves a gap in research specifically targeting university-level academic texts and clearly defined metacomprehension strategies (Mousavinasab et al., 2018). The limitations of previous studies, including short-term designs, heterogeneous samples, an absence of clear control groups, and the lack of a comparison between the use of ITS with human tutoring and independent use, are addressed by the experimental approach with QtA (Zarzosa Escobedo, 2004) and the inclusion of a group with human tutoring. This rigorous evaluation of the effects on reading comprehension and metacomprehension in university students is a key objective of the study. Despite advances in ITS research and its application in higher education, there are still questions and challenges that require further exploration. Additional research is needed to design and adapt ITS to effectively address the specific needs of college students and enhance their metacomprehension. In addition, it is essential to examine how students use and perceive ITS, as well as their influence on students’ motivation and engagement in academic reading.

In summary, reading comprehension and metacomprehension are crucial skills at the university level. ITS based on information and communication technology present a significant opportunity to enhance these skills by delivering an interactive and adaptive learning environment. This research will focus on analyzing the impact of ITS on improving reading comprehension and metacomprehension in college students, as well as exploring their perceptions and experiences in relation to the use of these tools. It is anticipated that the findings of this study will contribute to the effective implementation of ITS within the university environment. Additionally, it aims to offer recommendations for their design and application.

3. Method

Using an experimental approach with a 3×2 mixed factorial design, this study explored differences in reading comprehension and metacomprehension among university students following the implementation of the “Questioning the Author” (QtA) intervention program, based on an ITS. The program was delivered in two formats: one with teacher support and another without it.

3.1. Participants

The sample comprised first-year university students. A total of 134 individuals participated in the study voluntarily. All participants signed informed consent forms before taking part in the research. The average age of the participants was 20.61 years (SD = 2.30). The sample consisted of 82.09% women and 17.91% men.

The students were randomly assigned to three groups. Experimental group 1 participated in the intervention with teacher accompaniment and included 44 participants, 77.27% of whom were female and 22.73% male. The average age of this group was 20.59 years (SD = 2.61). Experimental group 2 participated in the intervention without teacher accompaniment and comprised 49 participants, 79.60% of whom were female and 20.40% male. The average age of this group was 20.20 years (SD = 1.49). Group 3, the control group, included 41 participants, 90.24% of whom were female and 9.75% male. The average age of this group was 21.12 years (SD = 2.69).

The sessions were conducted during regularly scheduled class hours, so they did not represent an additional workload for the students. No extra assignments were given, and the intervention sessions took place within the first six weeks of the semester, thereby avoiding interference with exams or other scheduled assessments. The digital texts used were not extensive, and the QtA program enabled dynamic interaction with students, providing continuous feedback, which in turn facilitated engagement in digital reading activities.

3.2. Materials

Two reading comprehension texts were used as a pretest: “Astronomy and Telescope” and “Memory” (Burin et al., 2010; Piovano et al., 2018). These texts were selected because of their use in previous research and their structure, which included a general concept, subordinate concepts, details of the subordinate concepts, a problem related to the subordinate concepts, and a conclusion. After reading, students answered a questionnaire that included literal true-or-false questions, multiple-choice inferential questions, and a question assessing the situation model.

As a postest, the reading comprehension text “Instrument for Measuring Reading Comprehension in University Students” (ICLAU) (Guerra García & Guevara Benítez, 2013) was used. This text consisted of 900 words and included seven questions that evaluated the five levels of language: literal, reorganization, inferential, critical, and appreciation.

In addition, the Inventory of Metacomprehension Strategies (IEML) (Wong & Matalinares, 2011) was used as both a pretest and postest instrument to assess the degree of students’ awareness of the use of metacomprehension strategies during reading. The inventory consisted of 25 multiple-choice questions divided into three moments: before, during, and after reading. The reliability of the instrument was moderate (Cronbach’s α = .61).

The intervention program used was the Questioning the Author (QtA) software developed by Luis G. Zarzosa Escobedo and Guillermo Hinojosa Rivero (Zarzosa Escobedo, 2004). The program offered tutorial interaction based on ITS principals and was designed to improve strategic reading skills with expository texts used in social sciences and humanities.

The essential components of the QtA program were structured as follows:

-

Work window: Presented the instructions for conducting the activities interactively and provided the study material. This window was divided into sections.

-

Sections window: Displayed the number of sections into which the text was divided.

-

Question selection window: Contained the question selector related to the section being studied.

-

Section of questions to be solved: Presented the questions to be solved by the students.

-

Answer selection window: Provided the different answer alternatives to the questions posed.

-

Answer confirmation button: Used by students to confirm their selected answer.

-

Feedback window: Displayed a feedback message according to the student’s selected response.

-

Performance graph: Reported the performance achieved by the student in each section.

-

End-of-lesson button: Allowed the student to conclude the lesson.

In addition to these components, the program generated a record of the student’s performance, which was displayed in a spreadsheet. This record allowed for the evaluation of the students’ progress in the lessons and showed the number of attempts made on each question until the correct answer was reached.

It is important to mention that the QtA program was capable of incorporating any type of text, but in this study, a version specifically designed to teach strategic reading with expository texts from the social sciences and humanities was used.

3.3. Procedure

The procedure consisted of administering the pretest to each group prior to the implementation of the intervention program. The QtA program was then implemented, comprising a training session followed by five weekly work sessions. At the end of the program, a postest was administered to assess reading comprehension. The groups that received the intervention participated in the same program; however, group 1 had teacher accompaniment during the intervention sessions, while group 2 completed the program without teacher accompaniment or instruction. The control group did not receive any intervention and continued with their regular Oral and Written Communication classes.

3.4. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using a 3×2 mixed factorial design, with intervention condition (teacher-accompanied intervention, unaccompanied intervention, and control group) as the between-subjects factor and time of measurement (pretest and postest) as the within-subjects factor. For each dependent variable (reading comprehension and metacomprehension), a mixed-factorial ANOVA was conducted to assess potential differences among the groups and across measurement times, as well as to detect any interaction effects. Following the identification of significant results, post hoc comparisons were performed using Tukey’s test at a significance level of .05.

4. Results

4.1. Comprehension Level Analysis

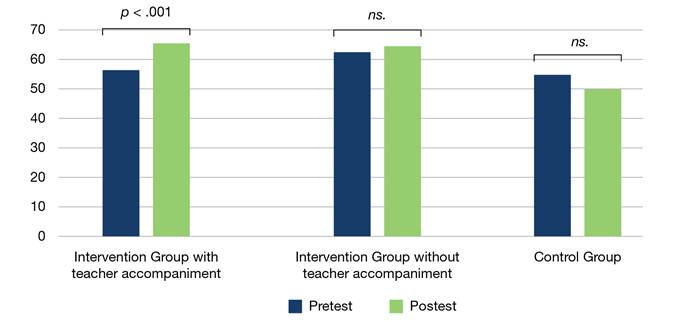

As for the results, Table 1 and Figure 1 present the descriptive statistics for each group in the pretest and postest conditions.

Descriptive Statistics of Reading Comprehension by Intervention Condition in Pretest and Postest

The analysis of variance revealed no significant difference between pretest and postest measurements, F(1,131) = 2.03, p = .16. However, a main effect of the intervention condition was identified, F(2,131) = 11.03, p < .001, η²p = .14. A post hoc analysis showed no significant difference between the intervention groups with and without teacher accompaniment (p = .23). However, significant differences were detected between the intervention group with accompaniment and the control group (p = .001), as well as between the intervention group without teacher accompaniment and the control group (p < .001).

Comparative Effects of Intervention with and without Accompaniment on Pretest and Postest Scores

In addition, interaction effects were found between the intervention condition and the measurement moment, F(2,131) = 6.56, p = .002, η²p = .09. Upon examining this interaction, the post hoc analysis revealed that the intervention group with teacher accompaniment presented significant differences (p = .001, d = .54) between the pretest (M = 56.16) and postest (M = 65.45) assessments. In contrast, the intervention group without teacher accompaniment showed no significant differences (p = .419), nor did the control group (p = .091).

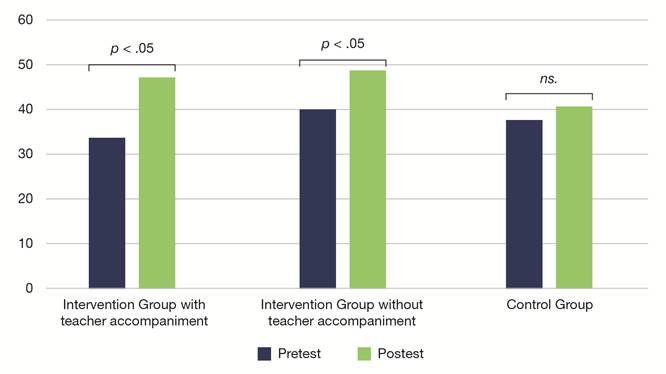

4.2. Reading Metacomprehension Level Analysis

The same statistical procedure was conducted as in the previous analysis, using the intervention condition and time of measurement as independent variables and the level of metacomprehension as the dependent variable. Table 2 and Figure 2 present the descriptive statistics of the metacomprehension measure for each group in the pretest and postest conditions.

Descriptive Statistics of Metacomprehension by Intervention Condition in pretest and postest

First, the differences between the groups were evaluated using an analysis of variance, which showed no significant differences, F(2,131) = 1.569, p = .212. However, a significant main effect of time was observed between pretest and postest conditions, F(1,131) = 36.007, p < .05, η²p = .21, as well as an interaction effect, F(2,131) = 4.445, p < .05, η²p = .06.

A subsequent post hoc analysis of the interaction was performed using Tukey’s contrast test. The results revealed that the intervention group with teacher accompaniment showed statistically significant differences between the pretest and postest conditions, in favor of the postest measurement (p < .05, d = .73). Similarly, the intervention group without teacher accompaniment also demonstrated significant improvement in the postest compared to the pretest (p < .05, d = .60). In contrast, the control group showed no significant differences between the pretest and postest measures (p = .253).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Correct comprehension of academic texts is one of the core activities that any university student must undertake throughout their studies (Kalbfleisch et al., 2021). However, students often struggle with this task, either due to a lack of metacognitive strategies (Bouknify, 2023; Khellab et al., 2022) or because the necessary cognitive processes for good comprehension are not activated (Juhaňák et al., 2025). Therefore, interventions that address this issue are required to foster academic literacy in students from their first years at university.

The main objective of this study was to examine the effect of a tutoring program based on ITS on the reading comprehension and metacomprehension of university students. An experimental study was conducted, comparing three groups of students (ITS with teacher accompaniment, ITS without teacher accompaniment, and a control group), measuring pre- and post-intervention levels of reading comprehension and metacomprehension. The results provided evidence in favor of implementing reading comprehension improvement programs, particularly when mediated by human tutors rather than relying solely on ITS. This finding is significant, given that the primary goal of the ITS-based training program is to enhance reading comprehension. On the other hand, a positive effect of ITS on improving metacomprehension was also observed. Thus, the main effects found centered on the role of the tutor in improving comprehension, and on the training program’s effectiveness in enhancing metacomprehension, with or without teacher accompaniment.

Findings suggest that ITS interventions coupled with teacher scaffolding exert stronger impacts on reading comprehension than standalone ITS implementations. This can be explained by the instructional mediation provided by teachers, who explicitly model comprehension strategies beyond what the technological tool can offer. In addition, teachers are able to provide targeted reinforcement and metacognitive cues, compensating for aspects of the program that may not be salient to learners.

The involvement of a human tutor is highlighted as essential for achieving the observed benefits, which can potentially enhance students’ academic performance and professional aspirations (Bernardo Zárate et al., 2021). These advantages are notably more pronounced when using a tutoring model based on evidence-based practices, such as the Reflective Individual Tutoring in Higher Education (RITHE) model. This model leverages insights gained from highly effective tutors and incorporates the theoretical and methodological principles of reflective learning (Pérez-Burriel et al., 2024). Regarding this first result, evidence supporting the implementation of reading comprehension improvement programs mediated by human tutors rather than ITS is highlighted. VanLehn (2011) suggests that the tutor effect can be explained through two hypotheses: feedback and scaffolding. These hypotheses are central to understanding the tutor’s role in academic coaching programs. The first hypothesis is based on the feedback that students receive from tutors. Human tutors typically provide highly interactive input at each stage of the teaching process, offering suggestions and addressing student errors (Bernardo Zárate et al., 2021). This results in more flexible responses compared to ITSs, which helps explain the findings from the first analysis.

The second hypothesis proposed by VanLehn (2011) considers scaffolding a central process in guiding the learner’s reasoning. Rather than providing new information, it involves a coordinated interaction between tutor and student, aimed at achieving better learning performance (Puntambekar, 2022). The combination of domain-specific intervention (present in both humans and ITS) and the ability to offer more complex responses and generate scaffolding (aspects unique to human tutors) likely explain the observed effects in this and previous studies (Nickow et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2019). In summary, current ITSs lack the capability to facilitate effective tutor-student cooperation. This collaboration, along with positive feedback, is essential for corrective processes and enhances students’ self-efficacy (Lin et al., 2022).

Regarding the second result, the positive effect of ITS on improving metacomprehension, it is essential to highlight that academic training programs designed to strengthen metacomprehension are effective when implemented through ITS, with or without human tutors (D’Mello & Graesser, 2023; Phillips et al., 2020). The findings indicate that reading metacomprehension improves after an ITS-based intervention program that guides students through the metacognitive process of reading academic texts. This improvement can be attributed to the monitoring and self-regulation strategies fostered by ITS. These strategies require students to explain the text to themselves, continuously monitoring their comprehension (McCarthy et al., 2018). ITSs induce situations in which metacognitive strategies must be applied, leading to better comprehension of academic texts (Serrano et al., 2018). However, it is crucial to note that the group without teacher accompaniment did not show a significant increase in reading comprehension, possibly because the human tutor guides the student in identifying when and how to apply the learned strategies. Knowing the metacomprehension strategy is not enough; it is also necessary to determine the appropriate time and context for its application during reading. In summary, the results indicate that ITS-assisted metacomprehension improvement programs are effective. Furthermore, the effects generated by ITSs could be amplified with longer implementation durations, as reported by Xu et al. (2019).

The main limitation of this study is the short duration of the program implementation. While Xu et al. (2019) report that most ITS studies last a minimum of eight weeks, the program in this study lasted only five weeks. Future research should explore longer implementation periods to investigate whether the reported effects are maintained or even enhanced. Additionally, other variables proposed by VanLehn (2011) that could mediate the impact of human tutors on reading comprehension improvement should be investigated, including personalized task selection, the type of dialogue generated with students, and interventions targeting motivation in educational contexts. Furthermore, item and learner characteristics may bias the performance metrics extracted by the ITS, as variations in item difficulty or format and differences in students’ cognitive or motivational profiles can influence observed gains (Hollander et al., 2022). Consequently, it is difficult to determine whether improvements stem solely from the ITS training or reflect underlying heterogeneity in tasks and participant abilities. This limitation suggests that future studies should control item uniformity and more thoroughly assess learner variability to better isolate the true effects of ITS. Another limitation is that the sample was predominantly female. If gender is considered to affect reading comprehension performance in university students, the study should be replicated with a gender-balanced sample.

ITSs can be significantly enhanced, and their potential maximized, through the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI). AI enables the profiling of individual learner needs, the identification of specific limitations, and the provision of adaptive, personalized feedback. Such capabilities create opportunities to advance research on tailored instructional interventions, thereby fostering the development of more personalized and data-driven learning environments.

In summary, the results provide evidence supporting the usefulness of academic training programs, whether implemented with human tutors or ITS. For comprehension, these programs improve reading comprehension when human tutors are present, while ITSs are effective in promoting metacomprehension strategies. These findings should be considered when designing academic interventions that involve human tutors and, ideally, complement them with ITS.

Acknowledgments

This study received no external funding. We thank all participants for their valuable contributions

References

-

Arner, T., McCarthy, K. S., & McNamara, D. S. (2021). iSTART StairStepper-Using comprehension strategy training to game the test. Computers, 10(4), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers10040048

» https://doi.org/10.3390/computers10040048 -

Atun H. (2020). Intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) to improve reading comprehension: a systematic review. Journal of Teacher Education and Lifelong Learning, 2(2), 77-89. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/1166467

» https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/1166467 -

Ayuso-del Puerto, D., & Gutiérrez-Esteban, P. (2022). La inteligencia artificial como recurso educativo durante la formación inicial del profesorado. RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 25(2), 347-362. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.25.2.32332

» https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.25.2.32332 -

Azevedo, R., Bouchet, F., Duffy, M., Harley, J., Taub, M., Trevors, G., Cloude, E., Dever, D., Wiedbusch, M., Wortha, F., & Cerezo, R. (2022). Lessons learned and future directions of MetaTutor: Leveraging multichannel data to scaffold self-regulated learning with an intelligent tutoring system. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 813632. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.813632

» https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.813632 -

Baker, L. (2016). The development of metacognitive knowledge and control of comprehension: Contributors and consequences. En K. Mokhtari (Ed.), Improving reading comprehension through metacognitive reading strategies instruction (pp. 1-33). Christopher-Gordon Publishers. https://r.issu.edu.do/Nwn

» https://r.issu.edu.do/Nwn -

Balla-Paguay, H. S., Parra-Rodríguez, N. M., Plaza-Escandón, H. D., & Cueva-Martínez, D. L. (2022). Aplicaciones digitales como herramienta de aprendizaje de la Contabilidad Básica en la Unidad Educativa Monseñor Juan Wiesneth. Prohominum,4(2), 349-361. https://doi.org/10.47606/ACVEN/PH0125

» https://doi.org/10.47606/ACVEN/PH0125 -

Barandica Sabalza, E. E. (2023). Metacognitive strategies and critical thinking in English learning: A systematic review in Scopus, Dialnet, and Redalyc databases. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 7(2), 857-876. https://doi.org/10.37811/cl_rcm.v7i2.5371

» https://doi.org/10.37811/cl_rcm.v7i2.5371 -

Bernardo Zárate, C. E., Rivera Rojas, C. N., Montes Yacsahuache, A. E., & Mancilla Curi, B. S. (2021). Tutoring and Training of University Students. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.31876/ie.v4i3.67

» https://doi.org/10.31876/ie.v4i3.67 -

Bouknify, M. (2023). Importance of metacognitive strategies in enhancing reading comprehension skills. Journal of Education in Black Sea Region, 8(2), 41-51. https://doi.org/10.31578/jebs.v8i2.291

» https://doi.org/10.31578/jebs.v8i2.291 -

Buckingham, D. (2015). Defining digital literacy - What do young people need to know about digital media? Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 1(4), 21-34. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2006-04-03

» https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1891-943X-2006-04-03 - Burin, D., Kahan, E., Irrazabal, N., & Saux, G. (2010). Procesos cognitivos en la comprensión de hipertexto: Papel de la estructura del hipertexto, de la memoria de trabajo, y del conocimiento previo. EnActas Congreso Iberoamericano de Educación (pp. 1-12).

-

Carretti, B., Caldarola, N., Tencati, C., & Cornoldi, C. (2014). Improving reading comprehension in reading and listening settings: the effect of two training programmes focusing on metacognition and working memory. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(2), 194-210. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12022

» https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12022 -

Castaño-Roldán, J. D., & Correa, D. (2021). Critical Reading with Undergraduate EFL Students in Colombia: Gains and Challenges. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 23(2), 35-50. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v23n2.89034

» https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v23n2.89034 -

Cerezo, R., Esteban, M., Vallejo, G., Sanchez-Santillan, M., & Nuñez, J. C. (2020). Differential efficacy of an intelligent tutoring system for university students: a case study with learning disabilities. Sustainability, 12(21), 9184. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219184

» https://doi.org/10.3390/su12219184 -

Choi, E., Kim, J., & Park, N. (2023). An analysis of the demonstration of five-year-long creative ICT education based on a hyper-blended practical model in the era of intelligent information technologies. Applied Sciences, 13(17), 9718. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13179718

» https://doi.org/10.3390/app13179718 -

Clinton-Lisell, V., Taylor, T., Carlson, S. E., Davison, M. L., & Seipel, B. (2022). Performance on reading comprehension assessments and college achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 52(3), 191-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2022.2062626

» https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2022.2062626 -

D’Mello, S. K., & Graesser, A. (2023). Intelligent tutoring systems: How computers achieve learning gains that rival human tutors. In Handbook of Educational Psychology (pp. 603-629). Routledge. https://r.issu.edu.do/vEv

» https://r.issu.edu.do/vEv -

Guerra García, J., & Guevara Benítez, Y. (2013). Validación de un instrumento para medir comprensión lectora en alumnos universitarios mexicanos. Enseñanza e Investigación en Psicología, 18(2), 277-291. https://r.issu.edu.do/c8r

» https://r.issu.edu.do/c8r -

Guo, L., Wang, D., Gu, F., Li, Y., Wang, Y., & Zhou, R. (2021). Evolution and trends in intelligent tutoring systems research: a multidisciplinary and scientometric view. Asia Pacific Education Review, 22, 441-461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-021-09697-7

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-021-09697-7 - Hollander, J., Sabatini, J., & Graesser, A. (2022). How Item and Learner Characteristics Matter in Intelligent Tutoring Systems Data. In Rodrigo, M. M., Matsuda, N., Cristea, A.I., & Dimitrova, V. (Eds.), AIED 2022 - 23rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (13356, pp. 520-523). Springer.

-

Juhaňák, L., Juřík, V., Dostálová, N., & Juříková, Z. (2025). Exploring the effects of metacognitive prompts on learning outcomes: An experimental study in higher education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 41(1), 42-59. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.9486

» https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.9486 -

Kalbfleisch, E., Schmitt, E., & Zipoli, R. P. (2021). Empirical insights into college students’ academic reading comprehension in the United States. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 51(3), 225-245. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2020.1867669

» https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2020.1867669 -

Kendeou, P., van den Broek, P., White, M., & Lynch, J. (2009). Predicting reading comprehension in early elementary school: The independent contributions of oral language and decoding skills. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(4), 765-778. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015956

» https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015956 -

Khellab, F., Demirel, Ö., & Mohammadzadeh, B. (2022). Effect of teaching metacognitive reading strategies on reading comprehension of engineering students. Sage Open, 12(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221138069

» https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221138069 -

Lin, C. C., Huang, A. Y., & Lu, O. H. (2023). Artificial intelligence in intelligent tutoring systems toward sustainable education: a systematic review. Smart Learning Environments, 10, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-023-00260-y

» https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-023-00260-y -

Lin, J., Singh, S., Sha, L., Tan, W., Lang, D., Gašević, D., & Chen, G. (2022). Is it a good move? Mining effective tutoring strategies from human-human tutorial dialogues. Future Generation Computer Systems, 127, 194-207. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2021.09.001

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2021.09.001 -

McCarthy, K. S., Likens, A. D., Johnson, A. M., Guerrero, T. A., & McNamara, D. S. (2018). Metacognitive overload! Positive and negative effects of metacognitive prompts in an intelligent tutoring system. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 28, 420-438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-018-0164-5

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-018-0164-5 -

Mousavinasab, E., Zarifsanaiey, N., R. Niakan Kalhori, S., Rakhshan, M., Keikha, L., & Ghazi Saeedi, M. (2018). Intelligent tutoring systems: a systematic review of characteristics, applications, and evaluation methods. Interactive Learning Environments, 29(1), 142-163. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1558257

» https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1558257 -

Nickow, A., Oreopoulos, P., & Quan, V. (2020). The impressive effects of tutoring on PreK-12 learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the experimental evidence (NBER Working Paper No. 27476). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27476

» https://doi.org/10.3386/w27476 -

Pérez-Burriel, M., Serra, L., & Fernández-Peña, R. (2024). How can we ensure limited individual tutorial time is reflective? The reflective individual tutoring model for higher education. Reflective Practice, 25(4), 467-483. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2024.2325413

» https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2024.2325413 -

Phillips, A., Pane, J. F., Reumann-Moore, R., & Shenbanjo, O. (2020). Implementing an adaptive intelligent tutoring system as an instructional supplement. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68, 1409-1437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09745-w

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09745-w -

Piovano, S., Irrazabal, N., & Burin, D. I. (2018). Comprensión de textos expositivos académicos en e-book Reader y en papel: influencia del conocimiento previo de dominio y la aptitud verbal. Ciencias Psicológicas, 12(2), 177-185. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v12i2.1680

» https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v12i2.1680 -

Puntambekar, S. (2022). Distributed scaffolding: Scaffolding students in classroom environments. Educational Psychology Review, 34, 451-472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09636-3

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09636-3 -

Ramirez-Altamirano, E. B., Salvatierra Melgar, A., Yauris-Polo, W. C., Guillen-Cuba, S., Huamanquispe-Apaza, C., & Lima-Roman, P. (2023). Metacognition as a Reading Strategy in Incoming University Students. Human Review. International Humanities Review / Revista Internacional de Humanidades, 21(2), 245-258. https://doi.org/10.37467/revhuman.v21.5052

» https://doi.org/10.37467/revhuman.v21.5052 -

Ruiz Domínguez, M. Á., & Area Moreira, M. A. (2022). Herramientas online para el desarrollo de la competencia digital del alumnado universitario. Profesorado, Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado, 26(2), 55-73. https://doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v26i2.21229

» https://doi.org/10.30827/profesorado.v26i2.21229 -

Sá, M. J., & Serpa, S. (2020). COVID-19 and the promotion of digital competences in education. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(10), 4520-4528. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.081020

» https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.081020 -

Sancho Gil, J. M., Ornellas, A., & Arrazola Carballo, J. (2018). La situación cambiante de la universidad en la era digital. RIED-Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 21(2), 31-49. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.21.2.20673

» https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.21.2.20673 -

Serrano, M. M., O’Brien, M., Roberts, K., & Whyte, D. (2018). Critical Pedagogy and assessment in higher education: The ideal of ‘authenticity’ in learning. Active Learning in Higher Education, 19(1), 9-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417723244

» https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417723244 -

Shafiee Rad, H. (2025). Reinforcing L2 reading comprehension through artificial intelligence intervention: refining engagement to foster self-regulated learning. Smart Learning Environments, 12(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-025-00377-2

» https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-025-00377-2 -

Uculmana Cabrejos, D. A., & Fernández Martínez, C. A. (2025). Metacognitive strategies in academic reading: University students’ perceptions from a phenomenological approach. Horizontes. Journal of Research in Educational Sciences, 9(37), 1214-1223. https://doi.org/10.33996/revistahorizontes.v9i37.979

» https://doi.org/10.33996/revistahorizontes.v9i37.979 -

VanLehn, K. (2011). The relative effectiveness of human tutoring, intelligent tutoring systems, and other tutoring systems. Educational Psychologist, 46(4), 197-221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2011.611369

» https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2011.611369 -

Vidal-Abarca, E., Gilabert, R., Ferrer, A., Ávila, V., Martínez, T., Mañá, A., Llorens, A.-C., Gil, L., Cerdán, R., Ramos, L., & Serrano, M.-Á. (2014). TuinLEC, an intelligent tutoring system to improve reading literacy skills/TuinLEC, un tutor inteligente para mejorar la competencia lectora. Journal for the Study of Education and Development: Infancia y Aprendizaje, 37(1), 25-56. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2014.881657

» https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2014.881657 -

Wang, H., Tlili, A., Huang, R., Cai, Z., Li, M., Cheng, Z., Yang, D., Li, M., & Fei, C. (2023). Examining the applications of intelligent tutoring systems in real educational contexts: A systematic literature review from the social experiment perspective. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 9113-9148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11555-x

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11555-x -

Wong, F., & Matalinares, M. (2011). Estrategias de metacomprensión lectora y estilos de aprendizaje en estudiantes universitarios. Revista de Investigación en Psicología, 14(1), 235 - 260. https://doi.org/10.15381/rinvp.v14i1.2085

» https://doi.org/10.15381/rinvp.v14i1.2085 -

Xu, Z., Wijekumar, K., Ramirez, G., Hu, X., & Irey, R. (2019). The effectiveness of intelligent tutoring systems on K-12 students’ reading comprehension: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(6), 3119-3137. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12758

» https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12758 -

Zarzosa Escobedo, L. (2004). Programa de cómputo para el desarrollo de la lectura estratégica en estudiantes universitarios. Universidades, 27, 39-51. https://r.issu.edu.do/8Fu

» https://r.issu.edu.do/8Fu -

Zhou, L., Shafique, H. M., & Ahmad, K. (2025). The development and implementation of strategies for promoting cultural literacy among university students in the digital environment. Information Development, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/02666669251314835

» https://doi.org/10.1177/02666669251314835

Fechas de Publicación

-

Publicación en esta colección

17 Nov 2025 -

Fecha del número

Jul-Dec 2025

Histórico

-

Recibido

05 Mayo 2025 -

Revisado

09 Set 2025 -

Acepto

14 Oct 2025 -

Publicado

17 Nov 2025

Comprensión lectora y metacomprehensión en estudiantes universitarios: impacto de un programa de Sistemas Inteligentes de Tutorías (SIT)

Comprensión lectora y metacomprehensión en estudiantes universitarios: impacto de un programa de Sistemas Inteligentes de Tutorías (SIT)